This research paper was presented at the Institute of Economic Affairs Kenya by Geoffrey Kerosi on 4th April, 2019 on the Big Four Agenda.

Abbreviations

CBA– Cost Benefit Analysis

CBK – Central Bank of Kenya

CMA – Capital Markets Authority

HF – Housing Finance

NCC – Nairobi City County

IDA – International Development Association

KMRC – National Mortgage Refinancing Company

KNBS – Kenya National Bureau of Statistics

Ksh – Kenya Shillings

MLF- Mortgage Liquidity Facility

NHC – National Housing Corporation

PPPs – Public Private Partnerships

SACCO – Savings and Credit Co-operative

WOCCU – World Organization Credit Union

1.0 Abstract

This research paper outlines the implications of housing as part of ‘The Big Four’ Agenda in Kenya. To arrive at the findings discussed here in, I largely relied on analysis of secondary sources of data. One of the largest implications of housing on trade is on housing bonds. This is not a new concept in Kenya since many companies have in the past made successful attempts to raise equity capital using bonds. However, for the masses out there, bonds are aliens. Hence, this research paper attempts to shed light on bonds and more specifically on housing bonds. The other important implication is that of housing on trading of housing construction materials as well as related services. Finally, the paper provides two case studies, one from Nigeria and the other from Sweden to give you a feel of what success social and affordable housing brings to the housing market.

2.0 Objectives

The objective of this research paper is to investigate the implications of housing as part of ‘The Big Four’ Agenda in Kenya.

3.0 Research Methodology

This research paper has been compiled based on analyses of secondary data contained in a variety of publications such as trade journals, newspapers, magazines, books, reports prepared by scholars, researchers and numerous publications on trade and housing as well as the linkage between the two.

The government plans to develop one million housing units in the next five years up to 2022. Out of these 800,000 units are categorized as affordable housing while 200,000 units are categorized as social housing. Hakijamii (2018) while researching on the State of Housing in Kenya discovered that the actual target is 500,000 housing units. That would mean that social Housing target is about 100,000 units in the next five years.

The government plans to finance these housing units to the tune of 10%, while the state owned National Social Security Fund (NSSF) is expected to contribute 30% funding. The balance of 60% is to be contributed by the private sector. These housing developments will be made up of 7,000 acres in five major towns of Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, Eldoret and Nakuru.

The planners, designers and architects of Kenya’s housing agenda have put across a number of strategies which they shall employ to achieve their objectives. First they are exploring innovative financing models such as Public Private Partnerships (PPPs), National Social Security Fund (NSSF) balance sheet and off plan sales; speeding up of transfer of titles and PPP; affordable home buyer financing through line of financing; credit line, a remortgaging company including background checks for persons in the informal sector and incentives to home buyers.

The Mortgage industry is expected to play a more active role in promoting access to affordable and social housing in Kenya. According to data from Central Bank of Kenya (2015), mortgage debt in Kenya is pegged at 3.15% of the Gross Domestic Product. The report further notes that housing finance in Kenya has not reached its potential because it is faced by a myriad of challenges. The Residential Mortgage Market Survey of 2016 by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) exposed some of the challenges facing mortgage industry in Kenya as: low levels of income, high cost of houses, high incidental costs, high interest rates on mortgages, lack of access to long term finance, difficulties in registration as well as titling of property among others.

In the back-drop of all the above mentioned challenges, Kenya’s national government has exactly 45 months remaining up to December 2022 to provide the promised half a million housing units. It is a wait-and-see situation in order to determine the effectiveness, efficiency of the government provision of social and affordable housing.

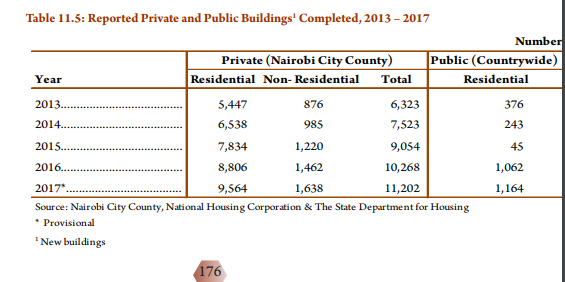

The time before the national government re-focused energies on housing, the country continued to benefit from public investment in infrastructure such as roads and railways, as well as heightened activity in the construction of public and private buildings.

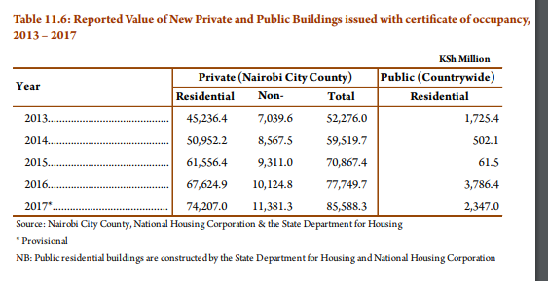

However, the value of public buildings completed by the State Department for Housing and National Housing Corporation (NHC) decreased from KSh. 3.8 billion in 2016 to KSh. 2.3 billion in 2017 according to the Economic Survey (2018 pp 174). This situation is expected to change drastically if housing agenda gets implemented according to plan.

In 2016/17, the approved expenditure for housing was KSh. 17.5 billion while actual expenditure stood at KSh. 16.5 billion, representing 94.3 per cent absorption of resources. At the sub-national level, the value of building plans approved by Nairobi City County (NCC) decreased from KSh. 308.4 million in 2016 to KSh. 240.8 million in 2017. During the same period, cement consumption decreased by 8.2 per cent to 5,789 thousand tonnes.

Table 11.6 shows reported value of new private buildings issued with certificate of occupancy in NCC and public buildings completed countrywide by the State Department of Housing and NHC. The value of new private buildings increased by 10.2 per cent from KSh. 77.7 billion in 2016 to KSh. 85.6 billion in 2017, mainly on account of a 9.7 per cent increase in the value of residential buildings. The value of public buildings completed decreased from KSh. 3.8 billion in 2016 to KSh. 2.3 billion in 2017 (Source page 177 Economic Survey 2018).

5.0 Results and Discussion

5.1 Financial Markets: Housing Bonds

According to research El-hadj M. Bah et al a number of governments and institutions are using housing bonds to raise resources for affordable housing construction projects.

“Kenya provides a good example of how financial institutions and property developers can raise funds through housing bonds. Shelter Afrique, the Nairobi-based pan-Africa housing finance institution, has successfully issued five housing bonds between 2005 and 2014, with amounts varying from Ksh. 500 million to Ksh. 5 billion. The tenors of these issues have ranged between three and five years, with coupon rates between 12.5% and 12.75%. Kenya’s favorable regulatory environment has precipitated the growth of this asset class.”

Kenya’s Capital Markets Authority (CMA) has a mandate to regulate the issuance of the capital market products such as shares and bonds. Since the private sector is expected to raise 60% of the financial resources required to provide the 500,000 units of housing, then, there is a high probability of a lot of bond trading in Kenya by the private sector.

This is not going to be the first time but we are likely to see plenty of activities from now to 2022. CMA approved housing bond issued on October 2010 (1st tranche) by Housing Finance (HF) valued at Ksh. 10 billion. To show you that a lot is happening, the first tranche mentioned above was over-subscribed by 41%. In October, 2012 the second tranche was issued and Housing Finance successfully raised Ksh. 5.2 billion. Again there was an over-subscription of 76 percent above the Ksh. 2.9 billion target. The researcher further notes that this efficiency of raising resources from the domestic capital markets in local currency leads to better terms for investors.

However, we have to note that not all housing bonds turn successful. For instance in 2014 Home Afrika (a property development company listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange) was forced to resort to the more expensive commercial loans after its first bond issue failed to raise Ksh. 500 million. Based on the past success stories by the firms we have mentioned above we cannot blame liquidity in the market. Therefore, the challenges facing Home Afrika lies elsewhere, maybe in the firm’s then declining profitability and weak performance.

Several analysts predict that successful performance in the bond market will be determined by credibility, trust, respect and health balance sheets.

Going forward, we will see cooperatives engaging more in the housing construction industry. This is because mortgage re-financing facility will provide them with the pre-requisite finances to boost their work. The challenges they are currently facing notwithstanding, the SACCO sector is the largest in Africa according to the World Organization of Credit Unions (WOCCU) report of 2014 which ranked Kenyan SACCOS at position 11.

Kenya’s Mortgage Refinancing Facility was launched on April 2018 by the National Treasury.

“The KMRC was an initiative of Kenya National Treasury and the World Bank to support affordable housing agenda by providing secure, long-term funding to the mortgage lenders, thereby increasing the availability and affordability of mortgage loans to Kenyans,” Henry Rotich Cabinet Secretary of National Treasury.

The Kenya Mortgage Refinancing Company (KMRC) will receive equity capital contributions from government of Kenya, international financial institutions such as World Bank among others. The National Treasury also urged various stakeholders to subscribe to the company’s equity in order to become beneficiaries of its services.

In a worrying trend, most of government support on housing in Africa is provided through the supply side such as sale and rent below-market rates, provision of serviced land, construction of social housing and even free provision of housing units as is the case in South Africa. There is no demand side sub-subsidies in place to promote access to housing.

5.3 Trade of construction materials

According to the KNBS (2018), cement consumption decreased by 8.2 per cent from 6.3 million tonnes in 2016 to 5.8 million tonnes in 2017, an indication of a slowdown in growth of construction activity compared to the previous year.[1] This situation is likely to change with the start of serious implementation of the Big Four Agenda – Housing- in Kenya. Therefore, there is likely to be a housing boom presenting plenty of opportunities for retailers and wholesalers of cement, iron sheets, building blocks, steel, nails and paints among other construction materials.

[1] Kenya Economic Survey 2018 (pp. 20)

The biggest beneficiaries will be equity owners of major cement factories such as Bamburi Cement Limited, Mombasa Cement, East Africa Portland Cement Company, Savannah Cement, Africa Limited and National Cement among others.

5.4 Trade for services in the construction of houses

The national housing agenda is likely to create millions of jobs for engineers, architects, accountants, quantity surveyors, urban planners, plumbers, electricians, carpenters and casual laborers among others. There is need to improve training for various cadres of construction industry workers and enhance the skills and numbers of officials in relevant departments responsible for provision of housing. Many county governments have in the past complained about inadequate skilled personnel to provide quality services.

6.0 Case studies

6.1 Nigeria Mortgage Refinancing Company

-

Launched on January 2014

-

Received initial loan of $250 million from WBG and International Development Association (IDA);

-

Shareholders: Nigerian government, Nigerian Sovereign Wealth Fund; DFIs such as IFC and Shelter Afrique; Primary Mortgage banks and Commercial banks in Nigeria;

-

By Feb 2014, NMRC had raised USD$35.45 m as capital from shareholders in addition to the $250 million IDA loan;

-

NMRC is expected to raise capital in the bond market;

-

At the time of creating the NMRC, the government also established a parallel process of simplifying land titling and significantly reduced land registration cost;

-

18 out of 36 states in Nigeria agreed to fast-track land registration procedures and reduce other costs such as land charges from 15% to 3%.

-

NMRC plans to finance 400,000 mortgage loans in the coming 5 years;

6.2 Kenya’s housing agenda vs the Million Programme in Sweden

According to Nordstrom (2010), one of the best but controversial public housing project was Sweden’s One million Programme. The program was implemented between 1965 and 1974 by the then governing Swedish Social Democratic Party. The party’s mission was to ensure all citizens would access housing at affordable costs. Looking back you will realize that the Million Programme was the most ambitious housing programme globally considering that its’ architects and designers targeted to construct 1 million homes in a country with a population of 8 million people (1:8). In comparison, Kenya’s Housing Agenda which focuses on constructing 500,000 houses for a country with 45 million people (1:90). Prior to the commencement of the one million programme, housing shortage was one of the hottest social and political issue is Sweden. The government ended up building 1,006,000 new homes courtesy of the programme (high level of effectiveness and efficiency). In Kenya, if nothing changes, corruption and pre-mature politics is likely to bring the housing agenda to a sudden halt. Unlike Kenya’s supply-side only incentives, the Swedish government would bear 66% of the cost of houses designed for the lowest-income group. In addition to that, the Swiss government in their wisdom provided incentives for students, immigrants and blue collar workers to establish construction companies. A lesson we learn from this is that everyone should play a role towards achieving the delivery of 500,000 housing units.

The definition of social housing was much clearer in Sweden than in Kenya since they catered for the social component of housing by constructing churches, schools, nurseries, public spaces and meeting places. Most of the apartments in Sweden were of the “standard three room apartment” of 75 square meters to provide adequate space for a model family of two adults and two children; In Kenya, most of the apartments are single rooms, double rooms and one-roomed houses which make them inadequate to host large families.

First, Kenya Mortgage Refinancing Company can be used as a vehicle to achieve standardization in the mortgage market in Kenya by calling upon the 47 counties to reduce land rates and fast-track the approval of housing plans. Second, Kenya should learn from the mistakes made by other countries which have implemented social and affordable housing. Third, a lot economic benefits can be harvested from the housing agenda if all stakeholders can restrain themselves from corruption and negative politics.

8.0 Recommendations

a) There is an urgent need for Kenya to ensure that the Mortgage Liquidity Facilities (MLF) is working efficiently to support development of the mortgage market. These are special vehicles for providing long term funds to mortgage lenders. These facilities have the potential to develop domestic capital markets in developing countries where mortgage markets are still at the nascent stage. The MLFs “serve as intermediaries between primary mortgages banks and the bond market”. MLFs can raise more funds as a result of their healthy balance sheets.

b) A number of African countries have already established the MLFs to provide long-term capital for mortgage Financing: Tanzania, Egypt and Nigeria. Tanzania created the Tanzania Mortgage Refinancing Company (TMRC) in 2010. This important body was key in triggering several banks to join the mortgage market in the country. As at December 2010, there were three (3) banks in the mortgage market and as at December 2014 they rose to 19 banks.

c) There is need for government agencies and other stakeholder to conduct analyses which measure the cost-efficiency of government interventions in the housing sector. For instance what is the Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) of providing free land to investors, providing subsidies to housing construction companies among others?

d) Kenyans should stop politicizing development and instead focus on creating and pursuing ideologies (which are currently non-existent). Aisen, Veiga & International Monetary Fund (2010) argue that “political instability is regarded by economists as a serious malaise harmful to economic performance.”

References

Bah, E. M., Faye, I., & Geh, Z. F. (2018). Housing market dynamics in Africa.

Central Bank of Kenya (2016). Residential Mortgage Market Survey.

Government of Kenya (2017) “The Big Four” – Immediate Priorities and Actions for the new Term. Nairobi: The Presidency.

Government of Kenya (2018). Kenya Economic Survey 2018.

Nordstrom, B. J. (2010). Culture and customs of Sweden. Santa Barbara, Calif: Greenwood.

Aisen, A., Veiga, F. J., & International Monetary Fund. (2010). How does political instability affect economic growth?. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.